Lehigh University co-hosts a panel discussion on antimicrobial resistance with the World Health Organization

Swabbing the dorm showers of Lehigh University may not be the most popular way people wrap their heads around studying health, but for Rhema Hooper, ‘26, it was a tangible way to understand the impacts of microbiology in her own home.

Hooper attended a documentary screening about antimicrobial resistance early in her Lehigh career and was swept away by the video and intense discussion that followed. This would change the way she went about her Lehigh education — including making her shower a personal lab to study antimicrobial resistance.

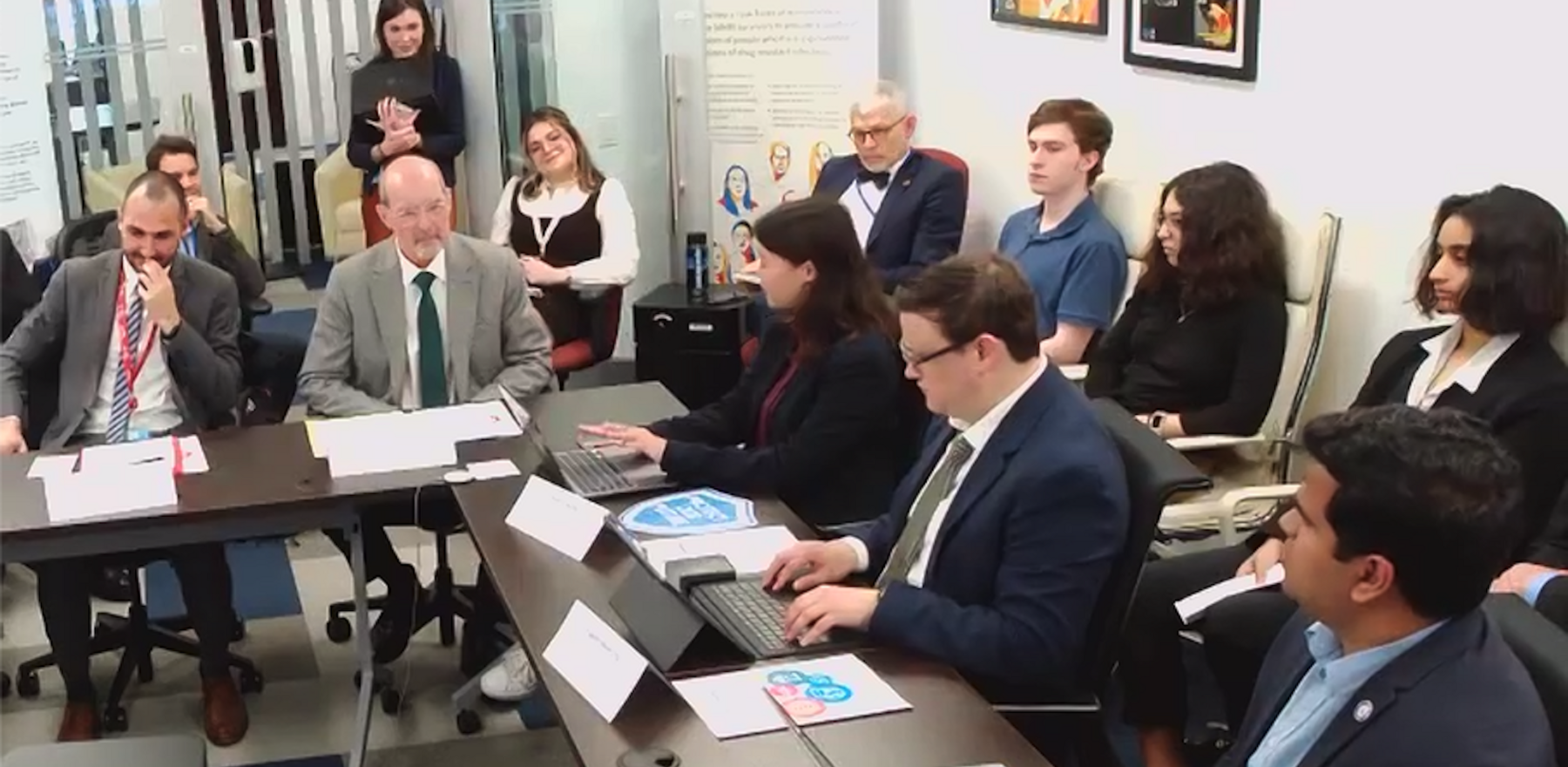

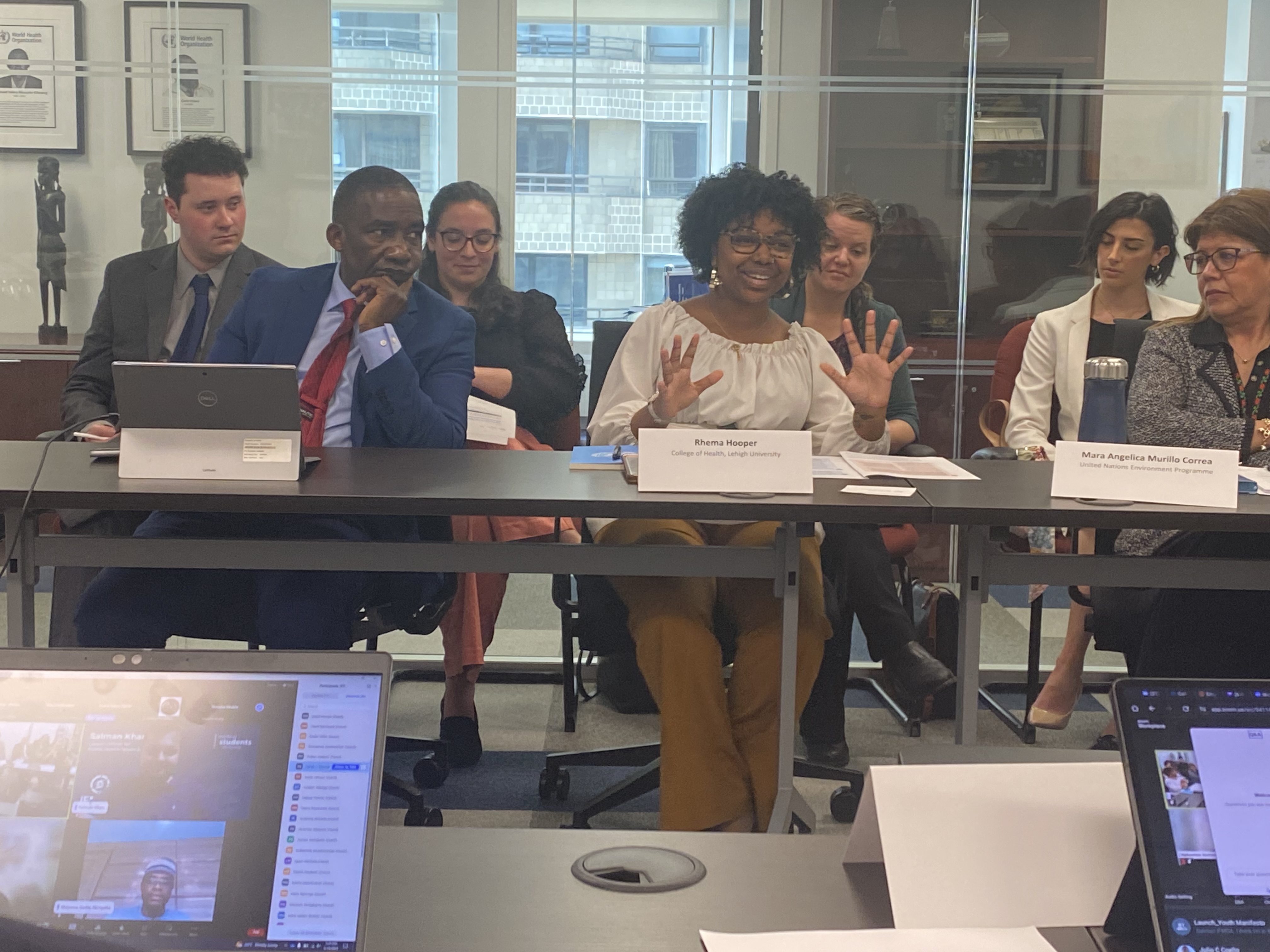

Lehigh students attended a panel discussion at the World Health Organization (WHO) headquarters in New York City on May 14 regarding antimicrobial resistance and the role youth play in leading efforts against the threat. The event was also broadcast online for viewers around the world.

Werner Obermeyer, the director of the WHO in New York, said this is the second high-level meeting regarding AMR since the first in 2016, and that Lehigh was invited to serve as the singular higher education institution to co-host the discussion.

Hooper said she first became interested in this topic after a documentary about AMR was screened at Lehigh. A dialogue was held afterwards with faculty members and students had done research on the subject, and they discussed how undergraduate students could get more involved.

"It completely blew my mind, and even transformed my own approach to my Lehigh education," Hooper said. "That experience was permanently instilled in me."

Obermeyer said he was delighted to have visited Lehigh earlier this academic year to speak with students and faculty on a range of topics including AMR, in addition to connecting his colleagues to Lehigh’s experts.

“I think Lehigh is an exemplar of what can be replicated on other campuses,” Obermeyer said. “I can foresee that there are chapters created on various campuses across the country (about AMR), of which Lehigh would be the pioneer.”

Five million people die every year from bacterial infections exacerbated by antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This data, in addition to a lack of research and development of new medicines that could alleviate this global issue, are why AMR or “superbugs” was identified as one of the top 10 global public health threats facing humanity today, according to WHO.

AMR is a phenomenon that occurs when active medications (antimicrobials) — used to treat viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections — are misused or overused, causing the infections to change over time. This means they stop responding to the medications, leading to difficulty or impossibility in dealing with the infections. The final result of this process is the greater spread of severe illnesses, diseases and even death.

Humans, animals, plants, and the general environment are threatened by AMR, making it a multisectoral and complex issue to tackle.

"Increasing emphasis is being placed on this One-Health approach, which is to look at how humans, animals, and the environment interact and intersect when it comes to the proliferation, selection, transport, and exposure to antimicrobial resistance," said Krista Liguori, a professor in Lehigh's College of Health who studies how environmental occurrence of AMR poses risks to human health. "It is an important framework for understanding the growing complexities around stopping AMR from becoming the next pandemic, but also an important framework through which we can look at other complex global issues."

Antibiotics are a main part of the current health system, Obermeyer said, so lacking these effective medications leads to a health system failure.

“Your health system cannot deliver what it should,” Obermeyer said. “That is the threat to modern medicine as we know it.”

This is where young people step up to the challenge, he said.

The Quadripartite Working Group on Youth Engagement for AMR, a group of 14 youth-representing individuals from 14 different countries founded last year, led the event last week in coordination with AMR stakeholders from across the world, including Lehigh.

The panelists included two representatives from the Quadripartite, another relevant civil society representative and Hooper, who represented the youth from Lehigh’s College of Health.

Leading the meeting and outlining the new Youth Manifesto for part of the United Nations General Assembly regarding AMR was Quadripartite member and pharmacist Audrey Wong.

She explained the top priorities identified by youth after consulting with groups from around the world. These areas included advocacy and engagement, education and capacity building, patient care, and using a One Health approach. The One Health approach involves multiple sectors and aspects of health in a holistic manner.

A theme from the panel aligned with this One Health approach by taking this global and complex phenomenon and dealing with it locally and tangibly.

“AMR is sometimes right in front of us but just needs a push” said Quadripartite member and doctor Augusto Barón, about understanding AMR.

Hooper said translating AMR to younger people in a tangible way, such as to students in middle and high school, can be an effective way to combat AMR in the long run.

She said explaining something as simple as the difference between antibiotic-treated and non-antibiotic-treated foods can open up minds earlier on to this daunting reality.

“This time, I am convinced, is your time,” said Javier Yugueros Marcos, the department head of the World Organisation for Animal Health, to the crowd.

Leaders from Malta, Barbados, India, Kenya, and the U.S. were in the room, all with a similar message to continue mobilizing and getting AMR on the tables of and in talks with political leaders.

Obermeyer said youth are opportunistically placed as both the leaders of tomorrow yet consumers of today, meaning they are directly affected by the choices of today’s leaders in the public and private sectors but can enact change in the near future.

“The youth have at their disposal so many tools across sectors that we don’t have in the WHO,” Obermeyer said, “It will be up to (them) to change the dial.”